The e-commerce revolution has snuck up on the interior design industry. Here’s how to get into the game.

Five years ago, it was rare—almost newsworthy—for a designer to sell something online. Now, designers sell everything from pillows, rugs and fabrics to matchboxes, ring lights and hedge clippers through digital channels. These days, it’s strange not to encounter that telltale “shop” button in the upper right-hand corner of a firm’s website. What changed?

There are three reasons why e-commerce is suddenly everywhere in the design industry. One is technological, one is cultural, and one is obvious. To start with the tech: In the aughts and early 2010s, even if designers wanted to sell things online, it was expensive and complicated. You had to hire a well-paid web designer to create the most basic portfolio website. Add in the need for a shopping cart, credit card processing, inventory management and the like, and back then, it could easily cost tens of thousands of dollars to set up even a simple e-commerce operation.

Now, not so much. A crop of off-the-shelf web-design tools like Squarespace, Wix and WordPress have matured into mass-market tools, while easy-to-use e-commerce platforms (there are plenty, but Shopify is the undisputed queen) have sprung up alongside them. It’s still a creative challenge to build a beautiful site, and there’s an entire cottage industry of consultants who help designers with their digital presence—but it’s no longer a $60,000 proposition to sell pillows online.

That’s the way. The will is trickier. The rise of tools like Shopify has fueled a surge of small-business e-commerce in a range of industries, but that change has come slower to design. Designers face the conundrum of preserving an elevated aesthetic while engaging in the messy business of dollars-and-cents commerce in the same digital space. Basically: “How can I attract a client who wants to spend $20,000 on a sofa while I’m selling $20 candles?”

It’s not that this issue has been solved, exactly—some designers still shy away from e-commerce for that very reason. But the hesitancy is fading away. Partially, it’s a big-picture cultural change. As a casual approach to life at home has become dominant, the lines between high and low have faded away, and “good design” no longer feels uniquely tied to a particular price point. Essentially, designers feel more comfortable doing both at once.

The rise of the designer-as-brand has also reshaped the landscape. Forty years ago, aspiring designers might have looked at Parish-Hadley—a boutique firm executing exquisite projects for a rarefied clientele—as the pinnacle of success. Now, young designers want to be Kelly Wearstler, a celebrated decorator, celebrity, influencer and business mogul who oversees a bevy of licensing partnerships. Selling stuff is simply part of the package.

Finally, there’s the obvious: COVID. Last year—especially in the early days of the pandemic, when it seemed as though the coming year might be disastrous—there was a rush of designers flocking to develop e-commerce to offset the anticipated loss in income. To be sure, many put those projects on pause when stay-at-home orders led to a boom in demand for design. But the pandemic-inspired acceleration of online shopping trends has inspired many designers to take a serious look at digital sales.

Case Study: The Instagram Merchants

Case Study: The Instagram Merchants

In a pandemic pivot, Susan and William Brinson invested in a Shopify site, designed it themselves, and scoured the internet for their favorite makers and artisan home brands, with a focus on holiday gifting. Within five months, they had cleared thousands of orders.

“It is crazy how many more designers have been asking me about setting up e-commerce in the last year,” says Angela Mondloch of Saffron Avenue, a creative agency that specializes in digital design. “Since COVID, it has shifted drastically: Probably 60 to 70 percent of designers who reached out have asked about a shop on their sites, if not more.”

In a way, it’s strange that it has taken so long for designers to get into the e-comm game. Their taste has long shaped the big-picture trends that determine what sells and what doesn’t on a national level. But for the most part, designers themselves have only been able to monetize their relationships with wealthy clients. Meanwhile, mass-market brands have fattened their pockets as everyday consumers look to designers for inspiration on Instagram, then shop retail to make it happen. It only makes sense for designers to try and get in on the action.

Just because it makes sense doesn’t mean it’s easy. Running a bustling e-commerce operation is every bit as complicated as running a successful store—and in some cases, more so. The good news is that there are more ways than ever for designers to experiment with online sales at various levels of commitment. Happy selling!

AFFILIATE MARKETING

By far, the simplest version of e-commerce is affiliate marketing—it’s so simple that some don’t even consider it to be “real” e-commerce. You put a link to a product on your site, and if someone uses your link to purchase the product, you make a small commission. What could be easier?

There’s an entire universe of companies set up to facilitate affiliate marketing, each with its advantages and disadvantages. However, all of them run into the same basic hurdle: It’s hard to make real money. Only a tiny percentage of followers will click the link. A still tinier percentage will make a purchase. And even then, the designer reaps only a minuscule slice (usually 3 to 5 percent) of the sale.

To that brutal math, add the fact that affiliate marketing works best when paired with great content, like a blog post or a photo shoot (it’s not as effective if you simply offer followers an unadorned list of stuff). This model is a great way to try your hand at online selling, but historically, only influencers with time to burn and tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of followers have made it truly pay.

There may be some change afoot there. A platform called SideDoor, launched in 2019, aims to bring the affiliate model to designers, but with trade margins built in. Using the tool, designers can offer pieces from vendors like Universal Furniture, Caracole and Stark Carpet through their sites while earning at least 30 percent of the sale price. SideDoor has some drawbacks (it doesn’t offer returns, for example), and it’s quite new (many designers told me they were excited to try it but that it was too early to judge its effect on their bottom line); still, it has compelling potential to make affiliate marketing a lucrative side hustle for designers who haven’t (yet) reached influencer status.

Case Study: The Brand Builder

Case Study: The Brand Builder

With a handful of rug lines under his belt, Michel Smith Boyd is no stranger to designing product. Now, he is in the process of slowly growing his e-commerce offering, in pursuit of building a brand that will carry him beyond the realm of day-to-day projects.

DROP-SHIPPING

Want to set up a robust online shop without spending a dime on shipping or renting out a single square foot of warehouse space? Drop-shipping is your move. Working this model, designers display goods on their site and process transactions themselves, but the order is ultimately fulfilled by the manufacturer. It’s more involved than affiliate marketing, but the basic premise is the same: The designer sells; someone else does the logistics.

The advantages of drop-shipping are obvious, and it’s one of the more common ways that designers establish an e-commerce presence. Syd and Shea McGee built their fast-growing McGee & Co. empire this way (they still sell other people’s goods more than their own); Kathy Kuo did the same. When you encounter a designer’s online shop and it’s stocked to the gills with product, chances are they’re drop-shipping a lot of it.

Though convenient, it’s not as simple as it sounds. First of all, you have to find vendors who are willing to do it. In the home world, where technology tends to lean old-school and logistics are onerous, not every brand is set up to work on a drop-shipping basis. And even if they are, manufacturers are often selective about who they’re willing to partner with. For that reason, designers who have long-term relationships with vendors

as buyers tend to have an easier time setting up drop-shipping arrangements. Trust is key.

Also, while someone else does most of the grunt work, it’s by no means hassle-free. Sellers have to stay on top of inventory, manage relationships with partners, calculate resale taxes, and deal with customers. (No matter what’s happening on the back end, the buyer will hold you responsible for the sale.) It’s not quite the same as operating your own warehouse, but don’t expect a drop-shipping store to run itself.

Finally, the big advantage of this system—that someone else is making and shipping the product—also has a big downside: You won’t control the delivery, and you can’t present the products in your own beautiful packaging. It’s hard to establish your luxury bona fides if your goods are getting tossed onto your customer’s lawns in lumpy cardboard boxes. Designers looking to build a brand tend to eventually move away from a drop-ship model

and develop their own product lines and logistics operations in order to make a better margin and gain more control of the customer experience.

Case Study: The Shopkeeper

Case Study: The Shopkeeper

When Darren Henault opened a home decor store in New York’s Hudson Valley, he also hired the former merchandising director of J.Crew to help him set up the shop’s accompanying e-comm site—proof that the game has changed for designers looking to dip their toe into retail.

HOLDING INVENTORY

You’re ready for the big time. You’re looking to—say it with pride!—hold inventory. Stocking product is both the simplest and most complex version of e-commerce. Simple because there are no fancy terms or sophisticated technologies underpinning it: You have something, you sell it online—presto, you’re done. Complex because that seemingly straightforward concept can get tricky fast.

The most obvious challenge is that it costs money to hold inventory—you’ve got to buy the product before you can sell it. You also have to store it somewhere, whether that’s a warehouse, the corner of a design studio, or a basement. Selling one pillow seems low-key, but to sell one pillow usually requires finding a cool, dry place to keep 50. Then there’s coming up with a system of keeping track of your inventory and getting it out the door to your customers.

Across the board, consultants will tell you that shipping, in particular, is the iceberg that tends to sink e-commerce ventures. Partially, it’s a psychological block. Most designers tend to focus on putting together an assortment of beautiful products and presenting them artfully—figuring out how to get it all into people’s homes is sometimes an afterthought. Even if you tackle shipping head-on, matching a wide range of inventory with the fairly limited packing options available is a hassle, to say nothing of actually stuffing things in boxes and getting them in the mail.

The challenges of holding inventory are many, but the rewards are often the most bountiful. Designers who carry their own goods often earn the highest margin on product and present the most compelling, customized experience. If you want your customers to receive their purchases in a colorful branded box, wrapped in tissue and lovingly tied up in a bow, this is the only way to go. It’s not for the faint of heart, but holding inventory can pay off in a big way.

Case Study: The Dabbler

Case Study: The Dabbler

Cara Woodhouse has built a buzzy design practice and developed licenses with trade brands like Nathan Anthony, and her projects can be found in glossy shelter publications with familiar names. How to turn all that energy into a real e-commerce business? The answer: It’s complicated.

ONE-OF-A-KINDS

You’re intrigued by the promise of e-commerce, but you’re not ready for complicated drop-shipping arrangements, you don’t happen to have a spare warehouse handy, and the idea of hawking affiliate links for scented candles makes you cringe. Fear not—there are other ways to get into the game.

One of the simplest: Designers who have developed custom pieces for clients during the normal course of business will often list versions of those items on their site along with a basic “email to inquire” button. It’s rudimentary and cumbersome by digital standards—and you’re not actually processing credit cards. But it’s a way to gauge interest in a product without getting into the complexity of transactional e-comm. It’s also not a bad way to start a conversation with a customer who could become a client.

Then, of course, there’s the secondary market. Much of the conversation about online sales tends to focus on new product, but if you’re an insatiable collector looking to lighten the load, you can certainly do it online—big players like Chairish, Incollect, Sotheby’s and 1stDibs all have tools that allow designers to host a “shop” to sell one-of-a-kind items on their firms’ websites. The world of online resale is also a bustling place full of startups, each with their own niche—Canopy auctions off wood furniture; The Local Vault does consignment sales for luxury home brands; and AptDeco and Kaiyo bring tech savvy to local buying and selling.

But if the mere thought of filling out a profile makes you yawn, there’s an even simpler option: It’s not at all unheard of for designers to film a quick Instagram story highlighting a piece they are looking to move, along with a caption that reads, “DM me if interested.” To the point, and surprisingly effective.

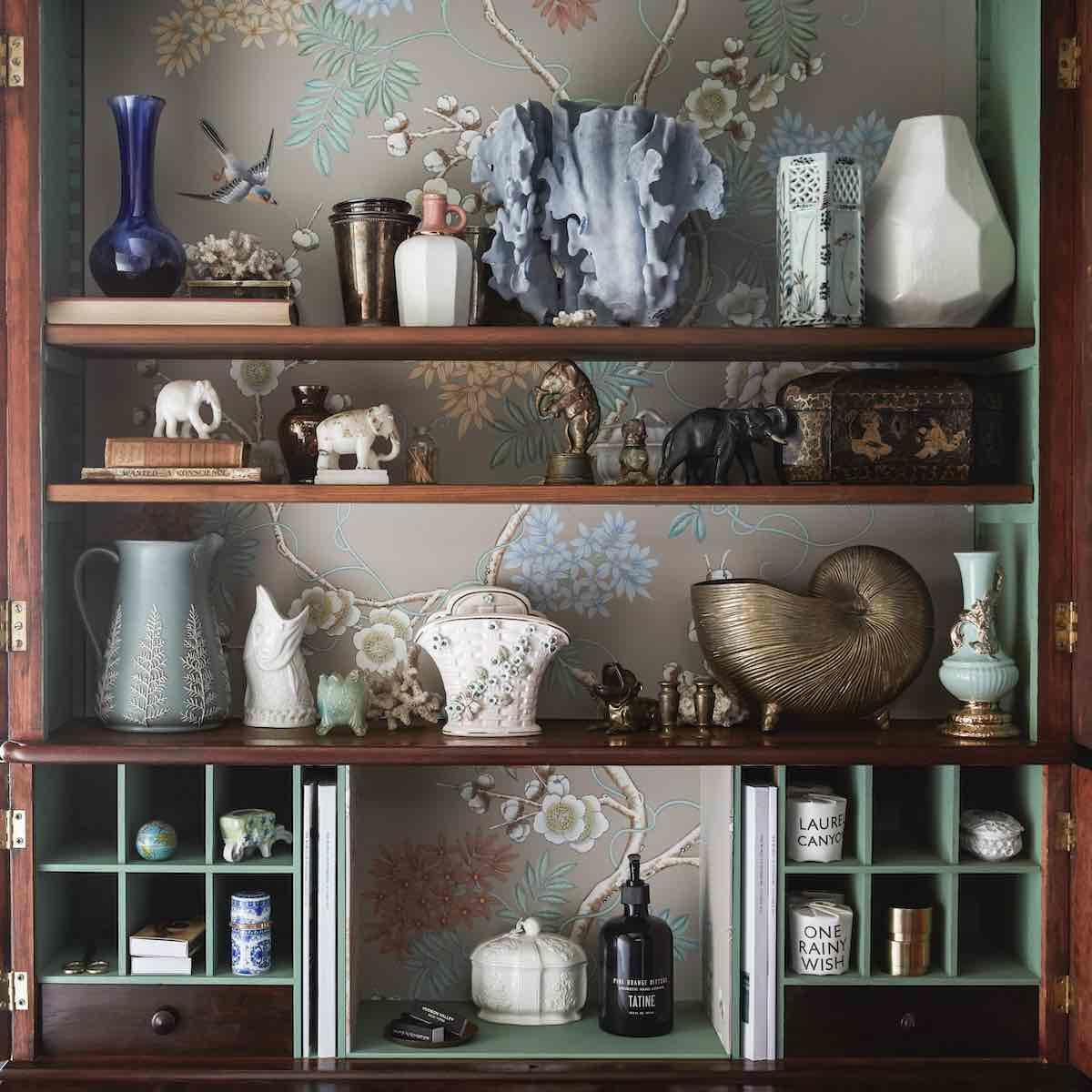

Homepage photo: A collection of handmade items from designer Darren Henault’s new store, Tent | Tom Moore